Have you ever noticed that some chords in music sound harmonious and stable, while others feel dissonant and tense?

In this section, we'll explore how differences in wave frequencies create these effects and examine the waveforms of various chords.

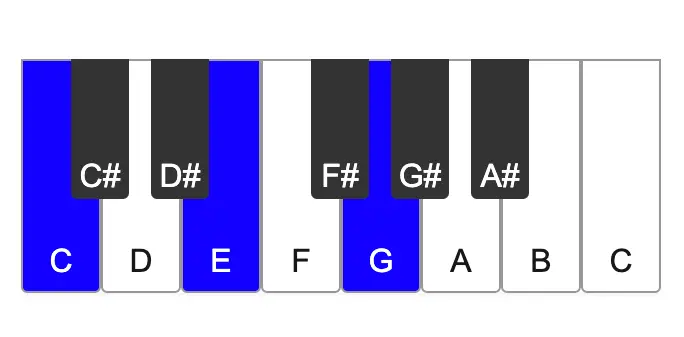

Below, C, D, E, F, G, A, B correspond to Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Si.

Play Some Sounds

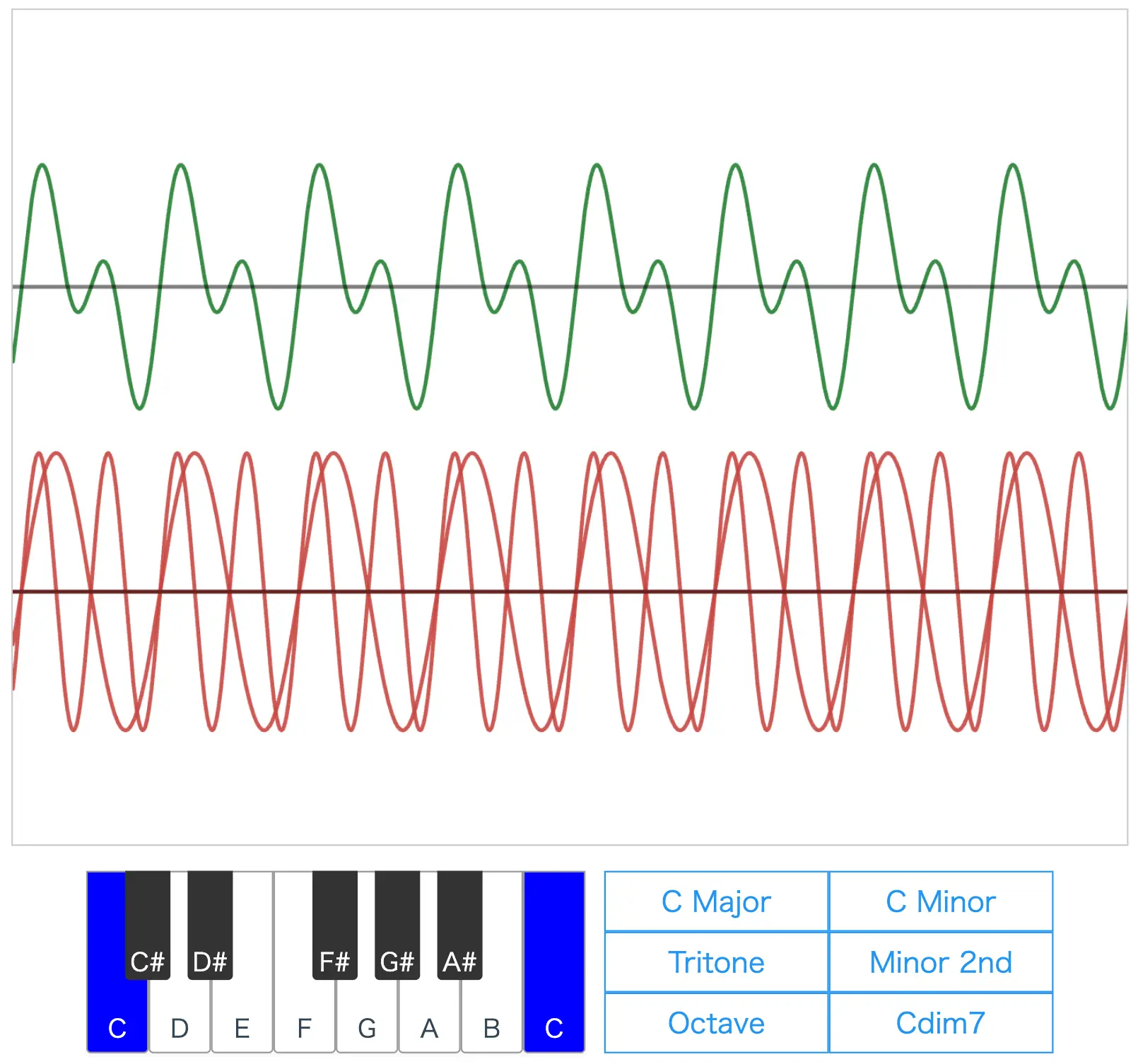

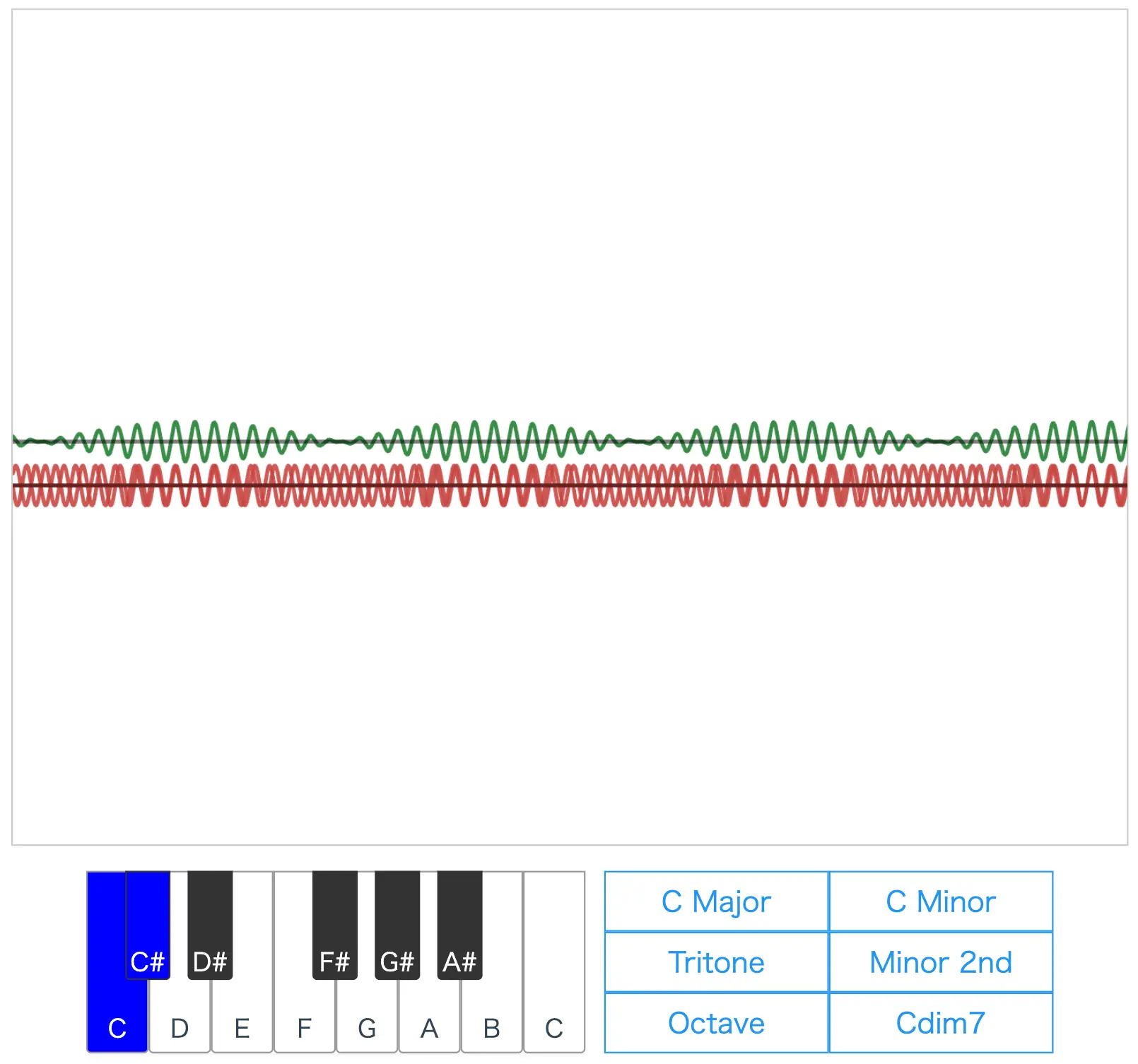

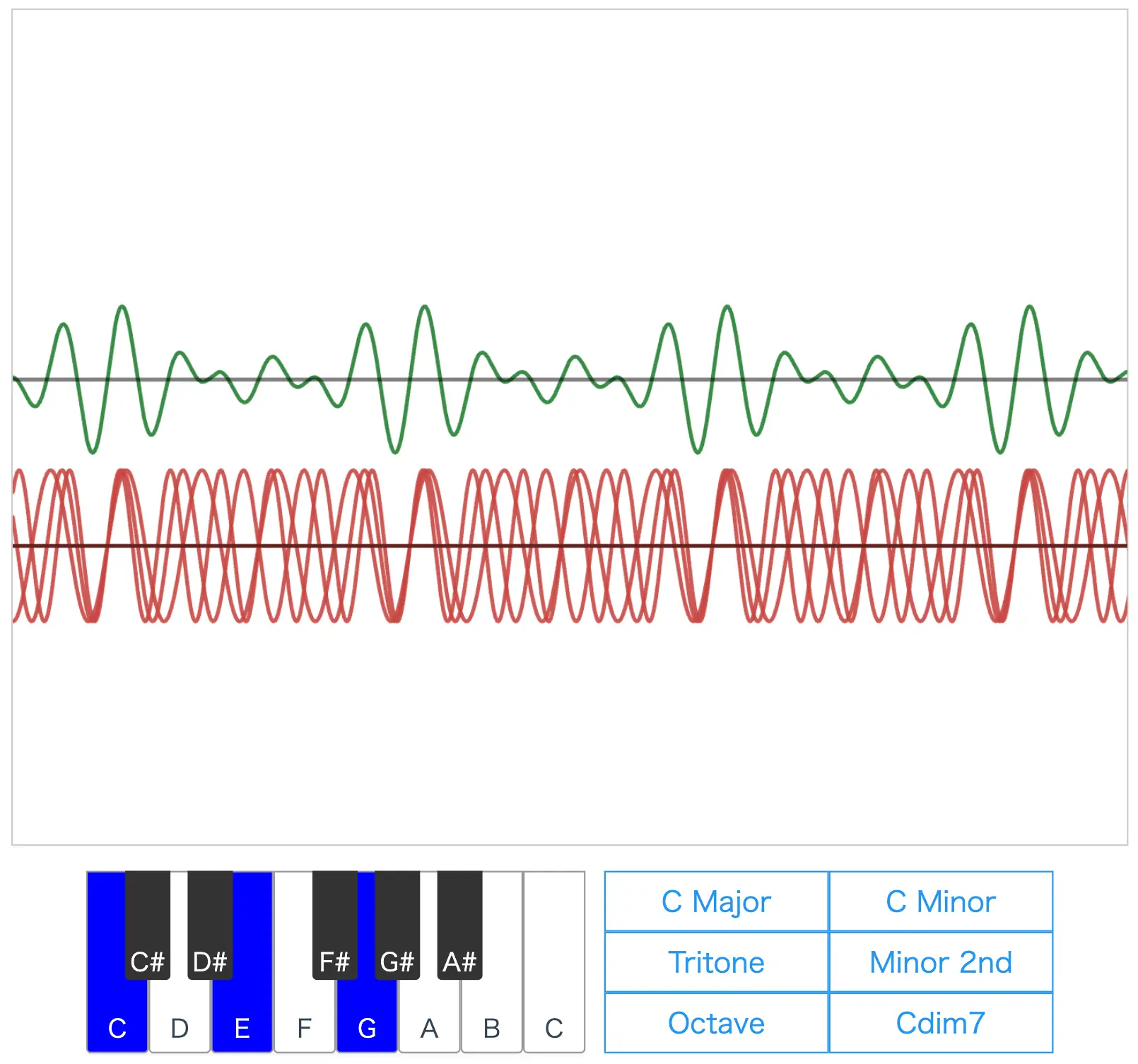

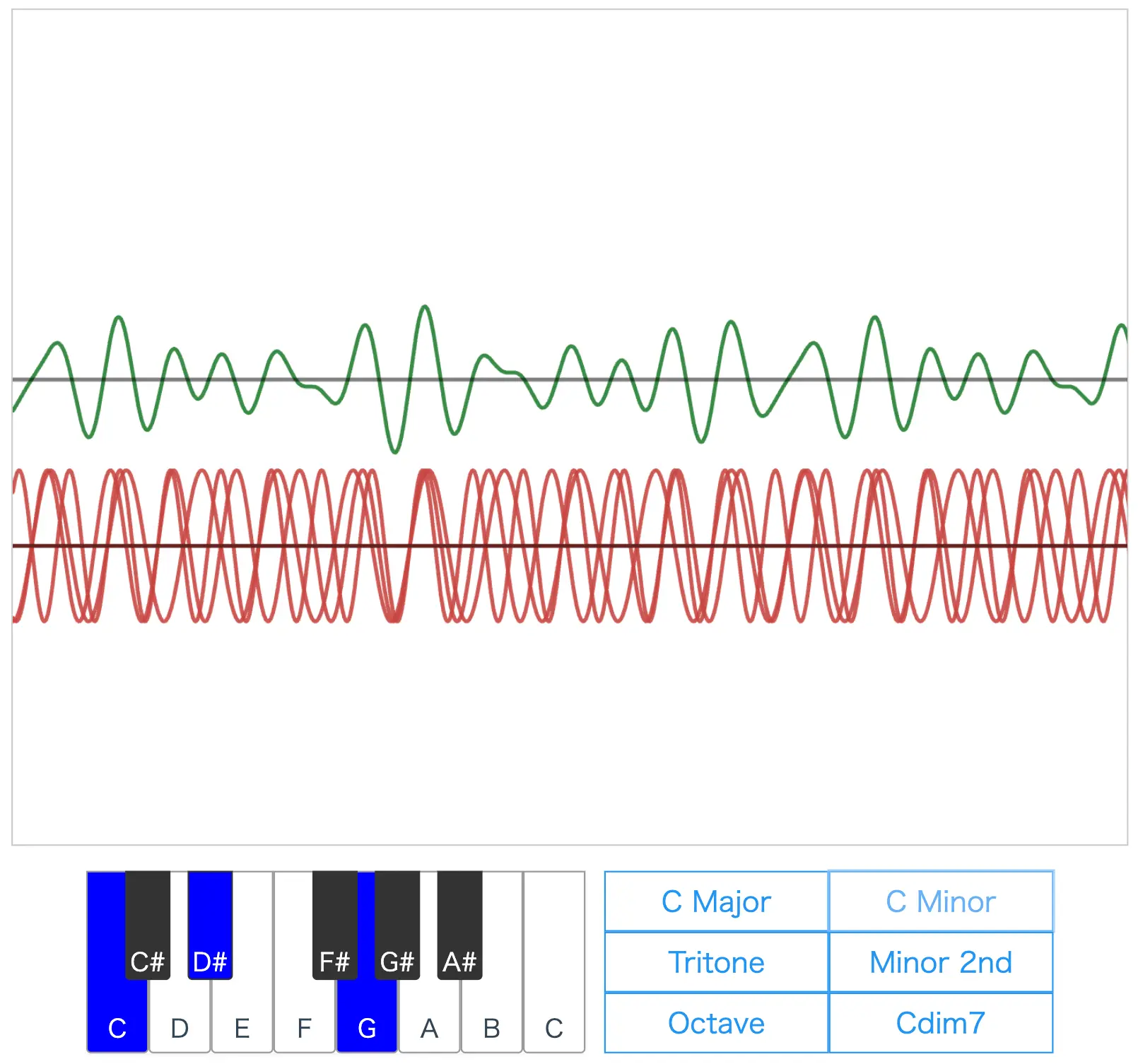

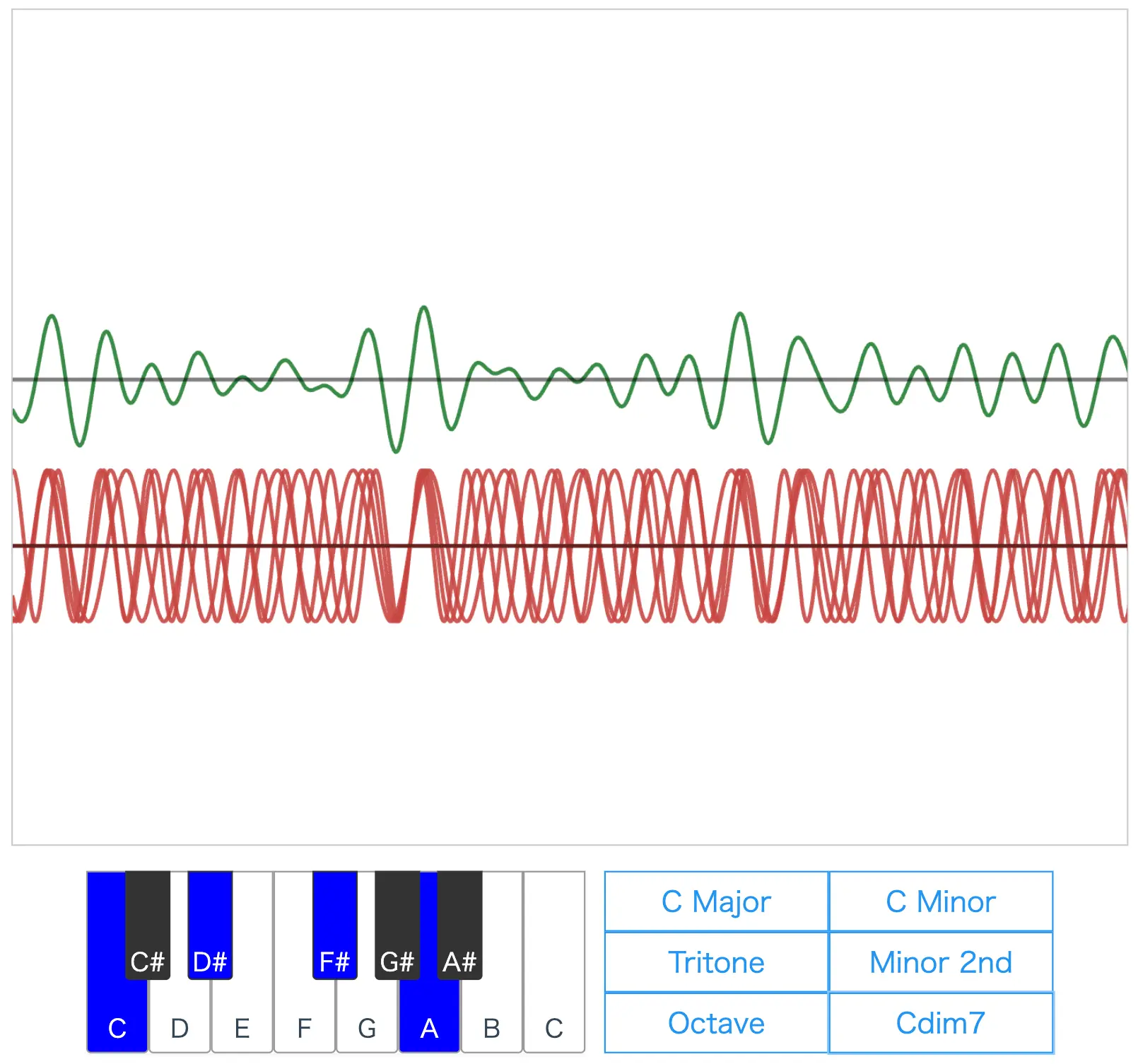

The top graph shows the actual sound wave (composite wave) you hear, while the bottom graph displays the individual sound waves of each note.

(If you're using an iPhone or iPad and can't hear any sound, please make sure your device is unmuted.)

- C

- DC#

- ED#

- F

- GF#

- AG#

- BA#

- C

Click on the piano keys or the buttons at the bottom right of the graph to see the waveforms of different chords. Then, press the play button to hear how they sound.

(To avoid sound distortion, newly added sounds during playback will be quieter than the ones already playing. If you want all sounds to play at equal volume, stop playback and restart it.)

The labels like "C Major" at the bottom right of the graph are called chords, which represent the names of the harmonies. Here, six major chords are listed, and their characteristics will be explained later.

The button at the top right of the graph lets you switch between just intonation and equal temperament. Temperament refers to the system used to determine the frequencies of each note based on a reference frequency. We'll dive deeper into this later.

How Are Note Frequencies Determined?

Many people know that the pitch of a sound depends on its frequency, but do you know how these frequencies are calculated?

First, a reference note and its frequency are chosen. A common reference is the middle A (La) at 440 Hz.

Then, the ratios of the frequencies of other notes to the reference frequency are determined, and all note frequencies are calculated based on these ratios. This system of defining frequency ratios is called temperament.

Here are two commonly used temperaments:

Equal Temperament

Equal temperament is a mathematically elegant system and is the standard in modern music.

Its key feature is that the frequency ratio between adjacent notes is constant, forming a geometric sequence.

First, the frequency ratio of an octave is set to 2. Then, the frequency ratios of adjacent notes are calculated accordingly.

Thus, the frequency ratio between adjacent notes is .

The frequency ratios for one octave based on a reference C (Do) are as follows:

Note | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Frequency Ratio | 1 | 1.059 | 1.122 | 1.189 | 1.26 | 1.335 | 1.414 | 1.5 | 1.587 | 1.682 | 1.782 | 1.888 | 2 |

Just Intonation

While equal temperament is mathematically convenient, its irrational frequency ratios can sometimes result in less harmonious chords.

To address this, just intonation adjusts the frequency ratios to be closer to rational numbers, which sound more harmonious. (We'll explain why rational frequency ratios sound more harmonious later.)

The frequency ratios for one octave based on a reference C are as follows:

Note | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Frequency Ratio | 1 | 16/15 | 9/8 | 6/5 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 45/32 | 3/2 | 8/5 | 5/3 | 16/9 | 15/8 | 2/1 |

1 | 1.066 | 1.125 | 1.2 | 1.25 | 1.333 | 1.406 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.666 | 1.777 | 1.875 | 2 |

While just intonation seems well-designed, its frequency ratios depend on the scale being used, making modulation and transposition challenging.

For example, if you try to modulate from the C Major scale (C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C) to to the D Major scale (D-E-F#-G-A-B-C#-D), the resulting scale will no longer adhere to just intonation.

Stable and Unstable Chords

What kind of waves produce what kind of sounds?

Use just intonation for the following examples to better understand the characteristics of the waves.

First, press the "Octave" button below the graph and then press the play button to hear the sound.

Adjust the graph's zoom level for better visibility.

You should hear a very stable sound.

Next, press the button labeled "Tritone" and listen to the sound.

You should hear a very unstable sound.

Finally, press the button labeled "Minor 2nd" and listen to the sound.

This sound is also very unstable, and you may hear beats. (This is often referred to as dissonance.)

The reasons for these different sound characteristics can be understood by examining the waveforms of the three examples.

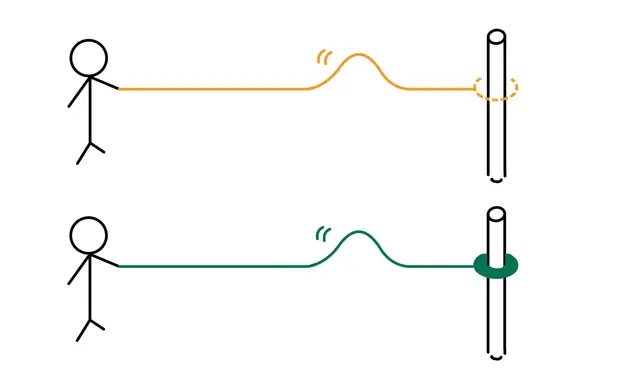

In the case of the octave, the frequency ratio of the two C notes is 1:2, a simple integer ratio, resulting in a composite wave that repeats the same shape over a short period.

In contrast, for the tritone and minor 2nd, the frequency ratios of the two notes are 32:45 and 15:16, respectively, which are more complex. As a result, the composite wave takes on a complicated shape that does not repeat easily.

Additionally, in the minor 2nd, the two notes are adjacent and have close frequencies, leading to audible beats.

Let's look at other examples.

Try listening to the sounds of "C Major," "C Minor," and "Cdim7" as well.

C Major produces a very stable sound, while C Minor and Cdim7 produce unstable sounds.

The frequency ratio of C Major is 4:5:6 (a famous ratio worth knowing).

The frequency ratio of C Minor is 10:12:15.

The frequency ratio of Cdim7 is 480:576:675:800.

Thus, you can see that the frequency ratio of C Major is very simple.

(Although C Minor has a simpler frequency ratio compared to Cdim7, making it a darker but more stable sound than the tense and unstable sound of Cdim7.)

Additionally, Cdim7 contains two tritones (C,F# and D#,A), which further contribute to its instability.

In summary, the simpler the integer ratio of the component frequencies and the shorter the period of the composite wave, the more stable the sound appears.