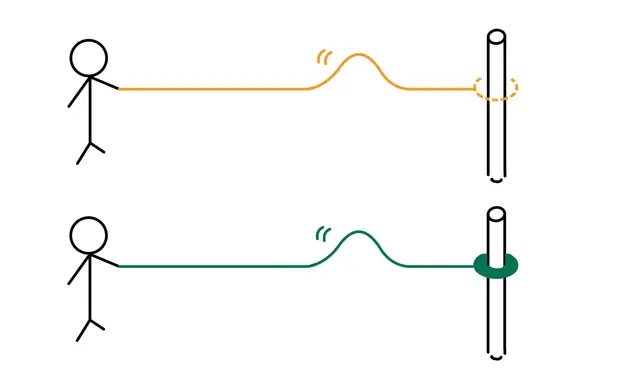

When waves reflect, the type of reflection—fixed-end or free-end—depends on the wave's nature.

If the end moves freely, the reflected wave's phase remains unchanged, resulting in free-end reflection. If the end is completely fixed, the reflected wave's phase shifts by , leading to fixed-end reflection.

But what happens in an intermediate state where the end's movement is partially restricted?

Or when the refractive indices of two media are identical for light waves?

When transmitted waves exist, the phase of the reflected wave is limited to 0 or . However, in cases of total reflection (no transmitted wave), the phase shift can take intermediate values between 0 and .

It's challenging to grasp this concept through text alone, so let's explore it using a graph!

Since this is a lengthy topic, this article will first focus on the case where transmitted waves exist.

When Transmitted Waves Exist

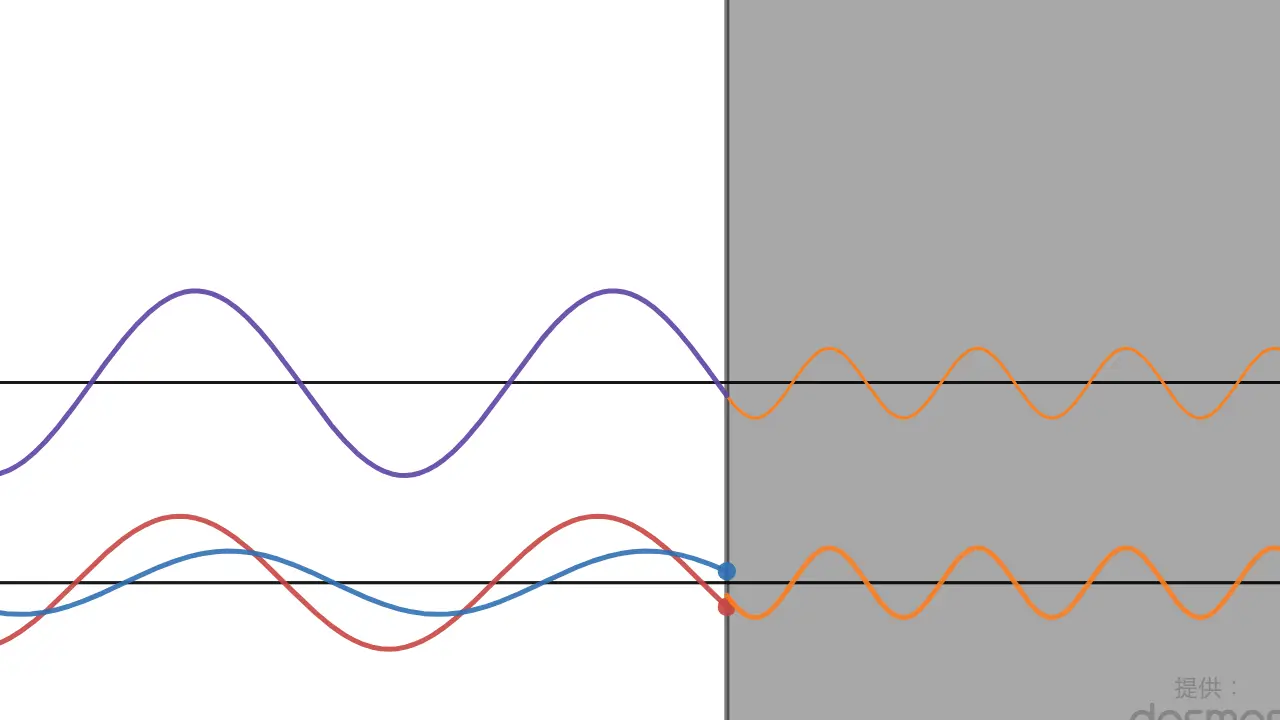

For light waves with transmitted waves, the graph looks like this:

(Here, when light enters a medium with a refractive index from a medium with a refractive index , we refer to as the refractive index ratio.)

The lower graph shows the incident, reflected, and transmitted waves, while the upper graph represents their composite wave, which is the wave we can actually observe.

Incident Wave | Reflected Wave | Composite Wave | Transmitted Wave・Composite Wave |

|---|---|---|---|

First, notice that when the refractive index ratio is at its maximum, the reflected wave's phase shifts by , resulting in fixed-end reflection. When the refractive index ratio is at its minimum, the phase remains unchanged, leading to free-end reflection.

In both cases, the reflectance approaches 100%, which is an important observation.

Now, let's examine what happens in the intermediate state.

Press the START / STOP button to pause the graph and adjust the refractive index ratio.

When the Refractive Index Ratio < 1

As you adjust the refractive index ratio from its minimum to 1, the amplitude of the reflected wave decreases. Notice that the phase of the reflected wave remains unaffected by the refractive index ratio and always has a phase difference of 0 with the incident wave (you can confirm this by focusing on the intercept, for example).

At this point, the end of the reflected wave aligns with the end of the incident wave, making it similar to free-end reflection.

In other words, compared to free-end reflection, only the amplitude of the reflected wave decreases.

When the Refractive Index Ratio > 1

As you adjust the refractive index ratio from its maximum to 1, the amplitude of the reflected wave decreases. Notice that the phase of the reflected wave remains unaffected by the refractive index ratio and always has a phase difference of with the incident wave (you can confirm this by focusing on the intercept, for example).

At this point, the end of the reflected wave is opposite to the end of the incident wave, making it similar to fixed-end reflection.

In other words, compared to free-end reflection, only the amplitude of the reflected wave decreases.

When the Refractive Index Ratio = 1

What happens when the refractive index ratio is exactly 1, the midpoint between free-end and fixed-end reflection?

The graph shows that the amplitude of the reflected wave becomes 0, and the reflectance also drops to 0.

A refractive index ratio of 1 means the medium through which the light wave passes does not change, so the light wave does not reflect and is entirely transmitted.

Considerations

Does this help clarify why the phase of the light wave changes abruptly by depending on the refractive index ratio?

Rather than saying the phase of the reflected wave changes abruptly by , it's more accurate to say that the amplitude of the reflected wave gradually decreases and reverses direction.

Reality is Closer to the Intermediate State

So, what is the refractive index ratio in real-world scenarios, such as light interference experiments?

A well-known light interference experiment is Newton's ring experiment (details omitted). In this case, reflection occurs between air and glass, and the refractive index ratio is approximately 1.46 (or about 0.68 in the reverse direction).

As shown in the graph, in this case, the reflectance is about 3.6%, so the displacement of the composite wave on the reflector does not behave like free-end or fixed-end reflection. Reality is closer to the intermediate state.

However, the key point is that the displacement of the reflected wave always changes by exactly or not at all. This means that in light interference experiments, you only need to consider whether the refractive index ratio is greater or less than 1.

Considering that the amplitudes of the incident and transmitted waves hardly change, it can also be understood that the amplitudes of the two interfering lights in the Newton's ring experiment are almost the same. (Both decrease significantly only during one reflection, but the degree of decrease is almost identical.)