This time, let's explore how electrons behave in a conductor using a simulation! We'll also introduce a fascinating phenomenon called electrostatic shielding.

Electron Simulation

Electrons Inside | Surface of the Conductor |

|---|---|

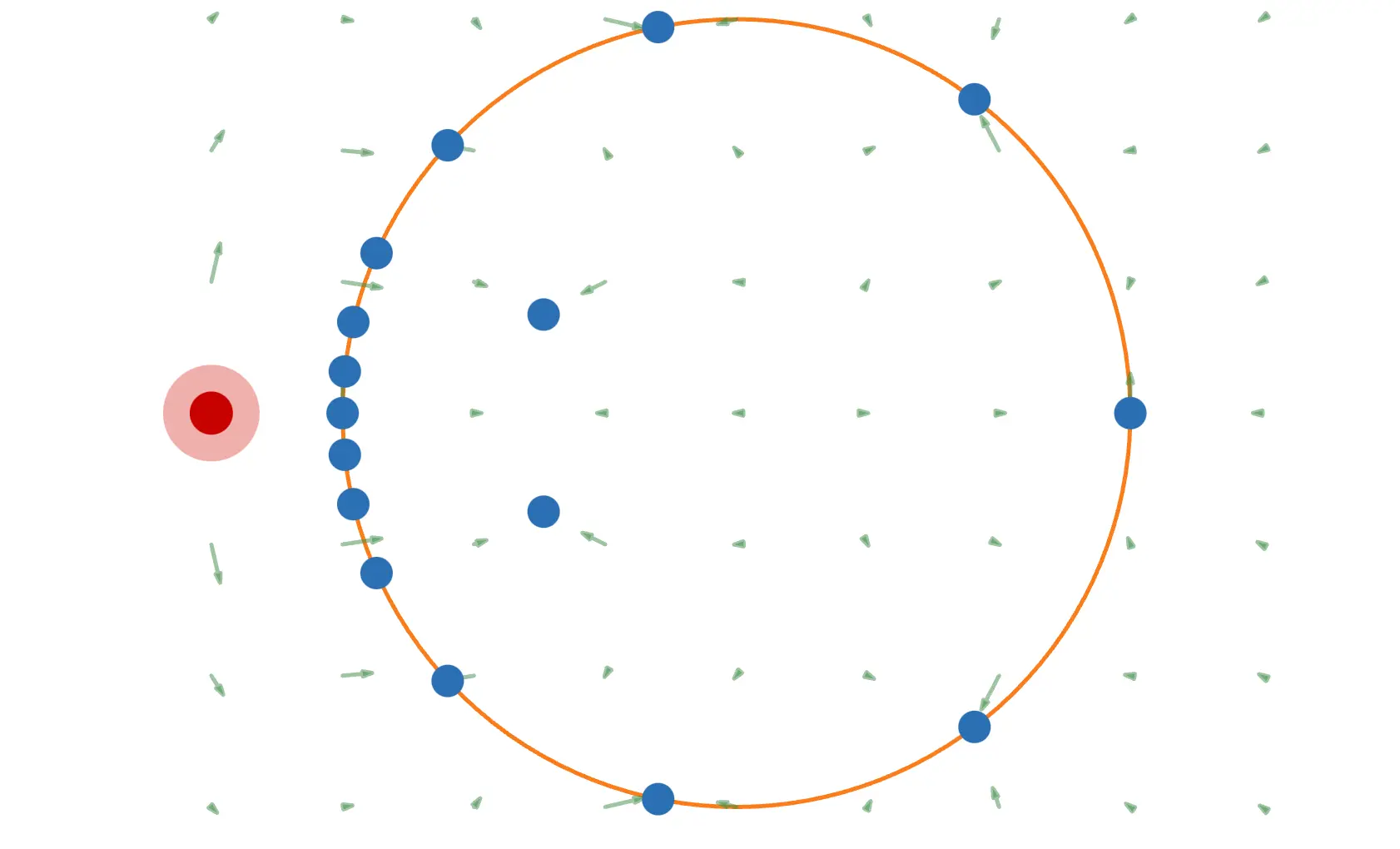

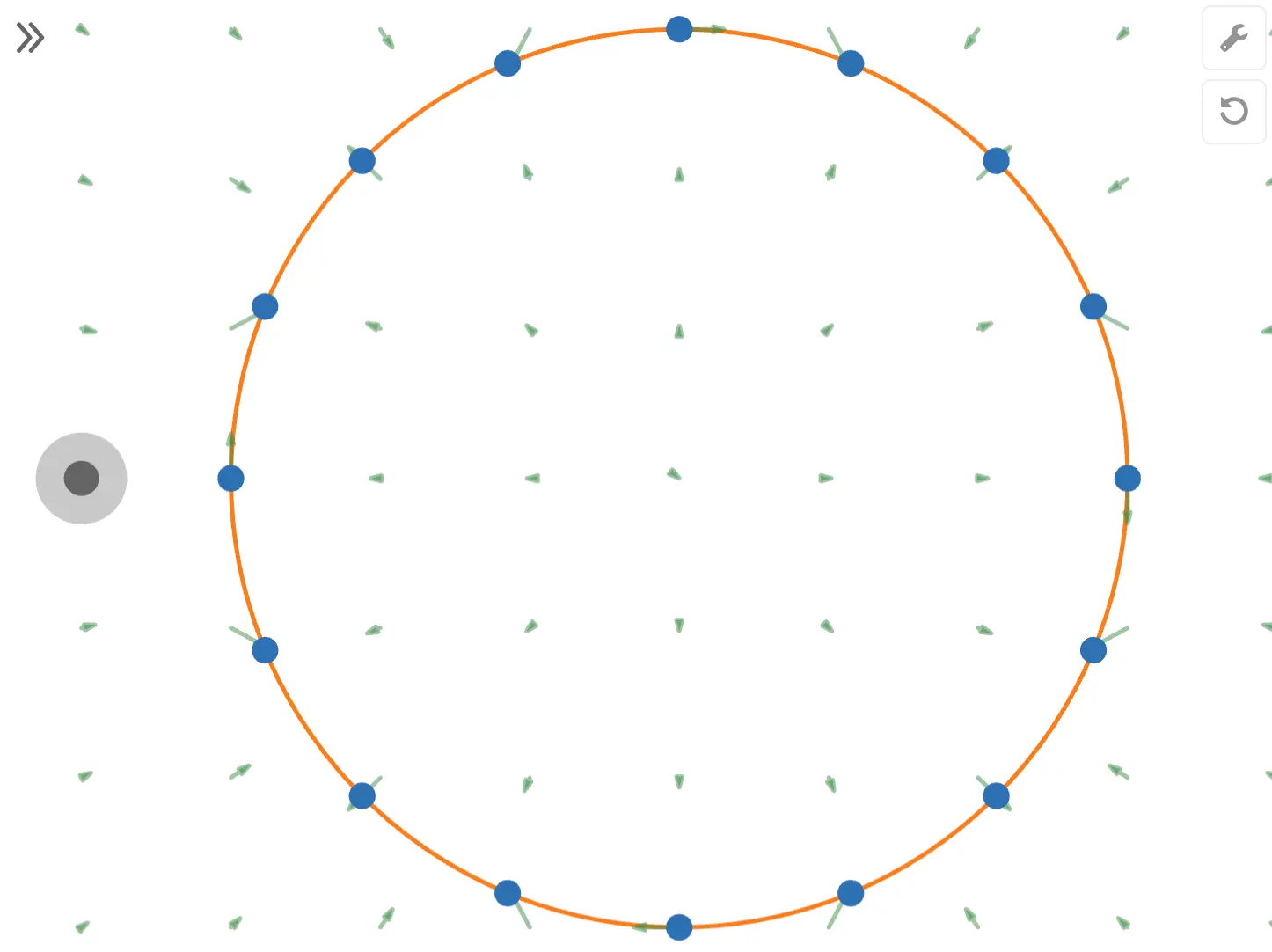

Click the START/STOP button to start the electron movement. Can you see them repelling each other?

Turning on the "Electric Field" switch will show the electric field in green. However, keep in mind that this might slightly affect performance.

Use the "External Charge" slider to create external charges. How do these charges influence the internal electrons and the electric field? You can also drag the external charge to move it around.

Characteristics of Conductors

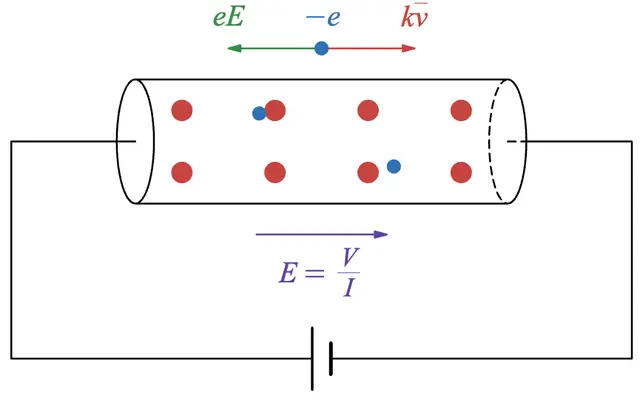

A conductor is a material that allows electricity to flow easily. Metals are a common example.

Inside metals, there are countless electrons called free electrons that can move freely. These free electrons are responsible for conducting electricity.

Conductors have the following key characteristics:

Characteristics of Conductors

- No electric field exists inside

- The potential inside remains constant

No Electric Field Inside

The first characteristic is that there is no electric field inside a conductor.

This happens because if an electric field were present, free electrons would move in a way that cancels it out. The force exerted by the field causes the electrons to redistribute until the electric field disappears.

Since there are so many free electrons in a conductor, they keep moving until the electric field is completely neutralized. As a result, no electric field remains inside.

The Potential Inside is Constant

The second characteristic is that the potential inside a conductor is constant.

This is directly related to the absence of an electric field. Potential refers to the energy per unit charge at a given position. Without an electric field, there’s no force acting on the electrons, so their energy becomes uniform. In other words, the potential is the same everywhere inside.

Another important property is that charges only appear on the surface of the conductor.

To be precise, the regions that are relatively positively or negatively charged are limited to the conductor's surface. This behavior is not perfectly replicated in the simulation, but it’s an important concept to understand.

Confirming with the Simulation

Let’s use the simulation to verify these characteristics.

After pressing the START/STOP button and waiting for a moment, turn on the switch to display the electric field.

Does it look like the image above? You should notice that there’s no electric field inside the conductor.

The same holds true even when external charges are present. Give it a try!

Electrostatic Shielding

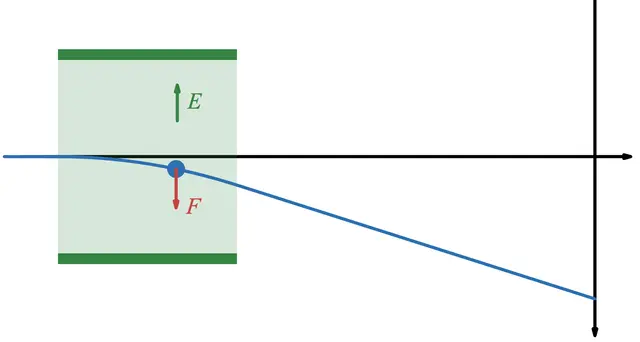

Thanks to these properties, a conductive container can block external electric fields. This phenomenon is known as electrostatic shielding.

As shown in the diagram, the external electric field lines are absorbed by the conductor's electrons. This prevents the field lines from penetrating inside, ensuring that no electric field is generated within the conductive container.

Rigorous Discussion (Advanced)

Using advanced physics concepts, we can rigorously prove electrostatic shielding.

Let the electric potential at position be , the charge density (charge per unit volume) be , and the permittivity be . The following Poisson equation applies:

Here, represents differentiation in the vector world. When expanded, it becomes:

represents partial differentiation, which is a specific type of differentiation. For now, you can think of it as regular differentiation.

The Poisson equation essentially states that the second derivative of the potential is proportional to the negative of the charge density.

Now, consider the inside of the conductive container. Since there are no charges inside, the charge density is . In equation form:

This is the case.

Let the potential of the conductor be constant and denote it as . Then, the potential on the boundary of the conductor (i.e., the inner surface of the conductor) satisfies:

(This is called the boundary condition.)

A potential that satisfies both is likely to be constant everywhere:

This can be considered.

In fact, when the boundary condition is known, the solution to the Poisson equation is uniquely determined. This can be mathematically proven! Therefore, this is the potential we are looking for.

A constant potential means that there is no electric field inside!