Do you know how electrons exist around the nucleus? This time, let's look at the appearance of electrons as envisioned by physicists Rutherford and Bohr through animations!

Animation

Nucleus | Electron |

|---|---|

As explained later, Rutherford thought that electrons orbit around the nucleus. Later, Bohr considered that electrons behave as waves.

Turn on the switches labeled Rutherford and Bohr to see the appearance of electrons as envisioned by each!

Press the switches labeled Absorption and Emission to make photons absorb or emit. This will also be explained later.

The mystery of atomic structure

The idea that matter is made up of tiny particles called atoms has been around since ancient times. However, how positive and negative charges are arranged within an atom remained a puzzle.

What was known back then was that atoms are electrically neutral because they contain equal amounts of positive and negative charges. It was also understood that most of an atom's mass is concentrated in its positive charges and that atoms absorb and emit electromagnetic waves at specific frequencies.

Based on this knowledge, various physicists proposed different models to explain atomic structure.

Different atomic models

Thomson's Plum Pudding Model

In 1904, J.J. Thomson introduced the Plum Pudding Model.

As the name suggests, this model likens the atom to a plum pudding, where small negative charges (electrons) are scattered like plums within a spread of positive charge.

Nagaoka's Saturnian Model

Also in 1904, Hantaro Nagaoka proposed the Saturnian Model.

This model suggested that electrons orbit in rings around a large positive charge, similar to the rings of Saturn.

Rutherford's Model

Ernest Rutherford conducted experiments by bombarding gold foil with particles, which led to the rejection of the Plum Pudding Model.

particles are small charged particles, and the experiment showed that most particles passed through the gold foil, while only a few were significantly scattered.

This result could not be explained by the Plum Pudding Model. In that model, the positive charge is spread out (thinly), so particles should pass through with little effect, and the phenomenon of some particles being significantly scattered could not be explained.

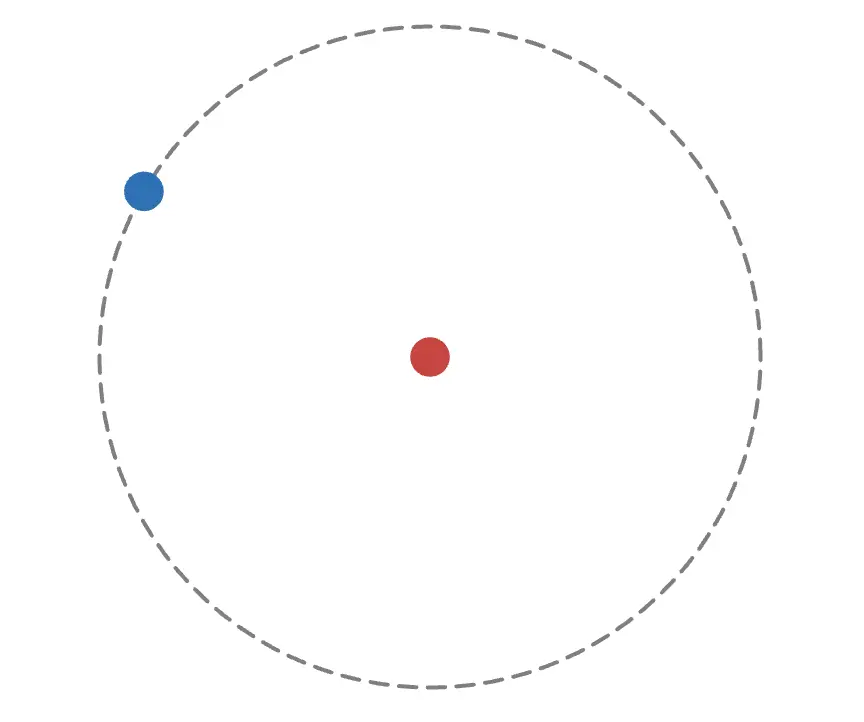

Therefore, Rutherford proposed a model where the positive charge (nucleus) is small and concentrated at the center, with electrons orbiting around it.

In this model, particles would only be significantly scattered when they collide with the small central positive charge, which explains the experimental results well.

This is a famous model taught in high school chemistry, but it has some difficulties.

Difficulty 1: Electrons fall into the nucleus

According to electromagnetism, a charged particle with acceleration emits electromagnetic waves and loses energy.

In Rutherford's model, electrons are in circular motion, so they have centripetal acceleration. This means they emit electromagnetic waves and lose energy.

Electrons that lose energy should slow down and fall into the nucleus, but this does not happen in reality.

Difficulty 2: Absorbed and emitted electromagnetic waves are continuous

It was known that atoms absorb and emit electromagnetic waves of specific frequencies.

However, in Rutherford's model, electrons can take any speed continuously, so the electromagnetic waves emitted by electrons can have any frequency. (The frequency of electromagnetic waves equals the number of circular motions per unit time.)

Bohr's Model

Bohr proposed a model that could solve these difficulties in Rutherford's model.

He suggested that electrons can only move on certain radii that satisfy specific conditions. The condition is:

This is called the quantum condition, where is the mass of the electron, is the speed of the electron, is the orbital radius, is Planck's constant, and is any natural number called the quantum number.

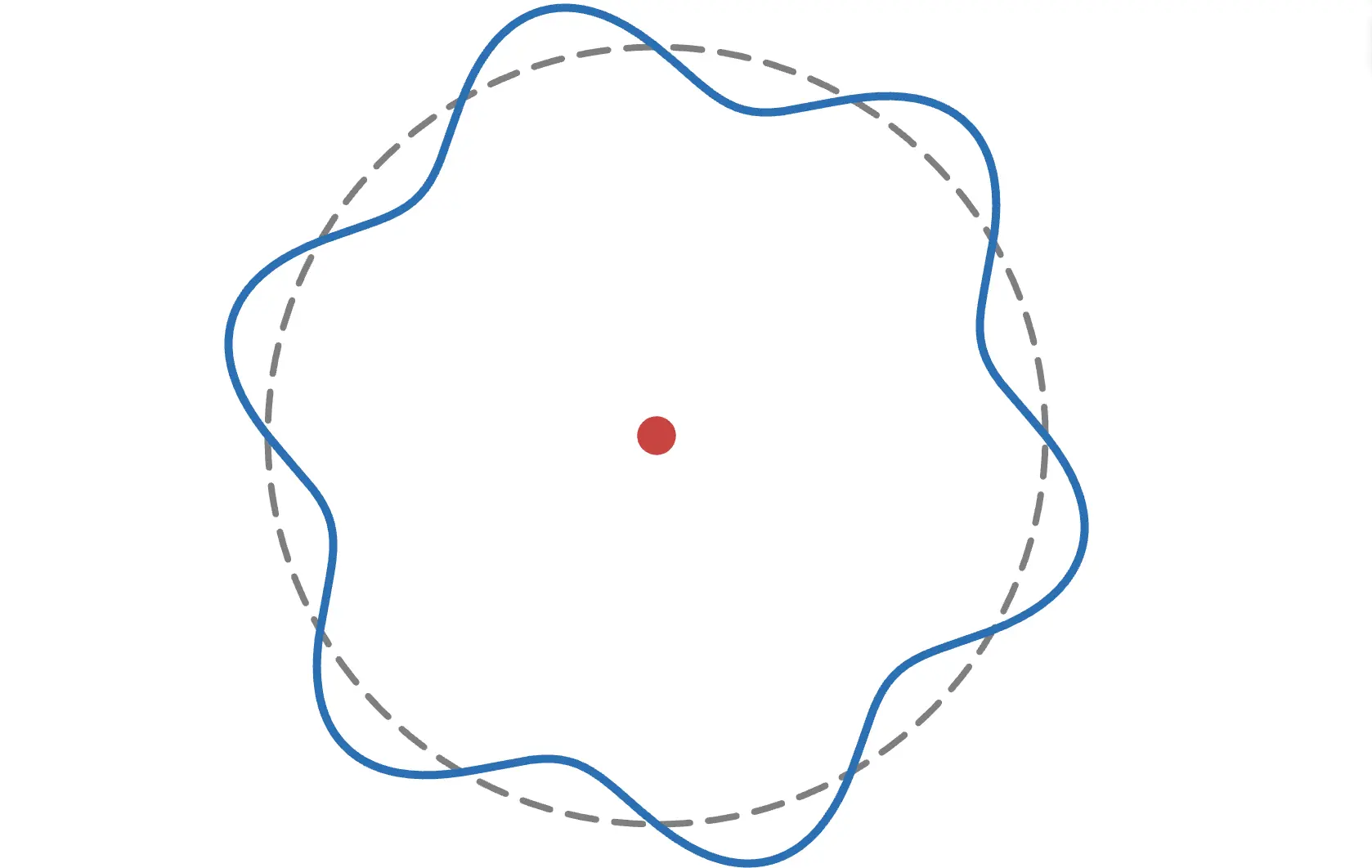

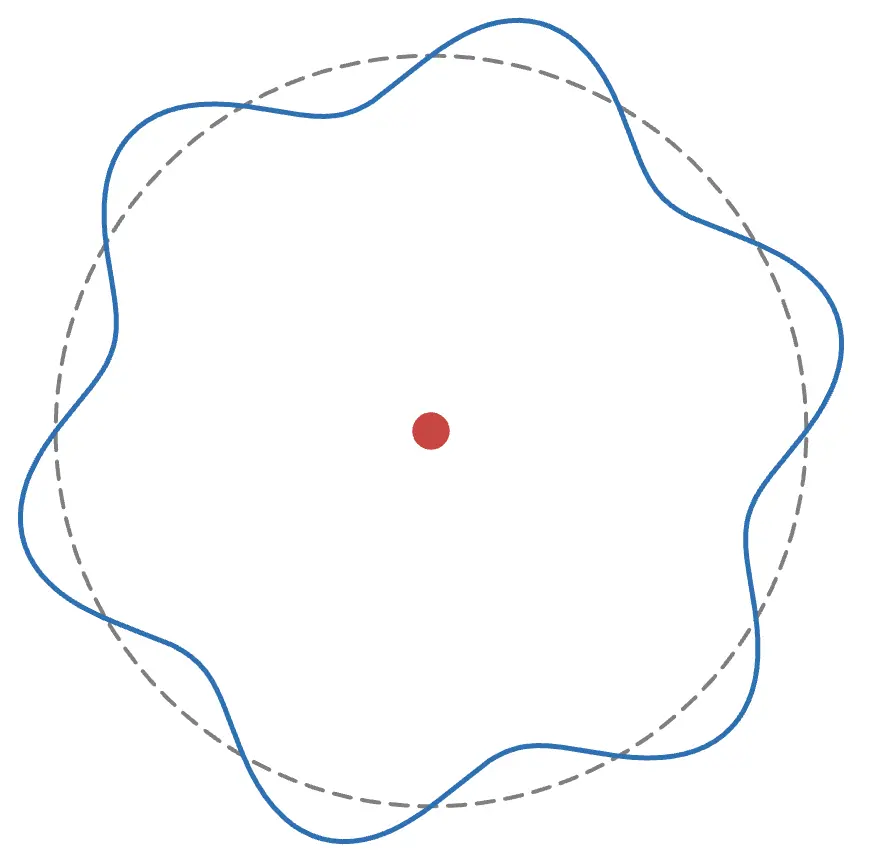

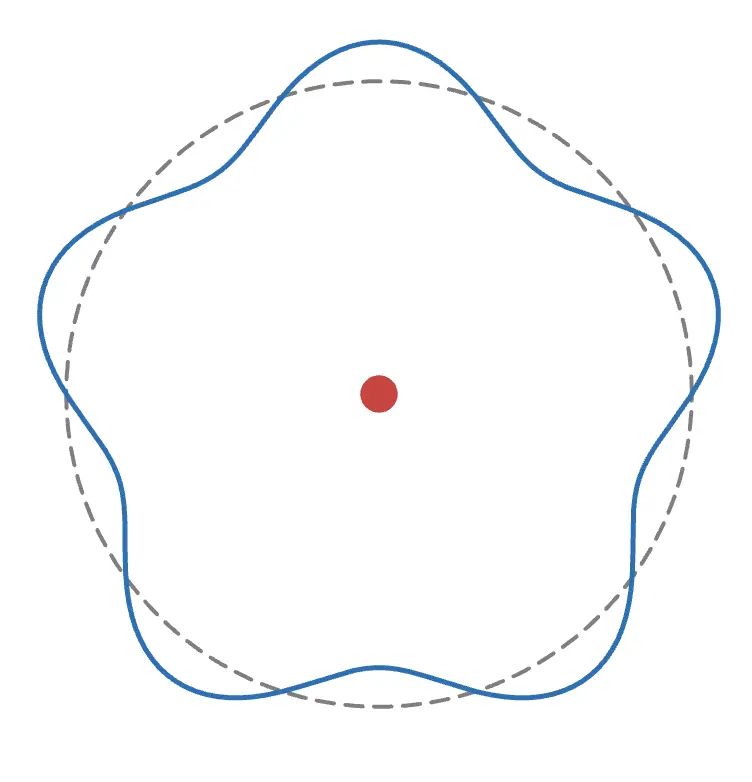

This may seem abstract, but considering that electrons have wave-like properties as matter waves, it can be understood thatelectrons exist around the nucleus as waves (standing waves).

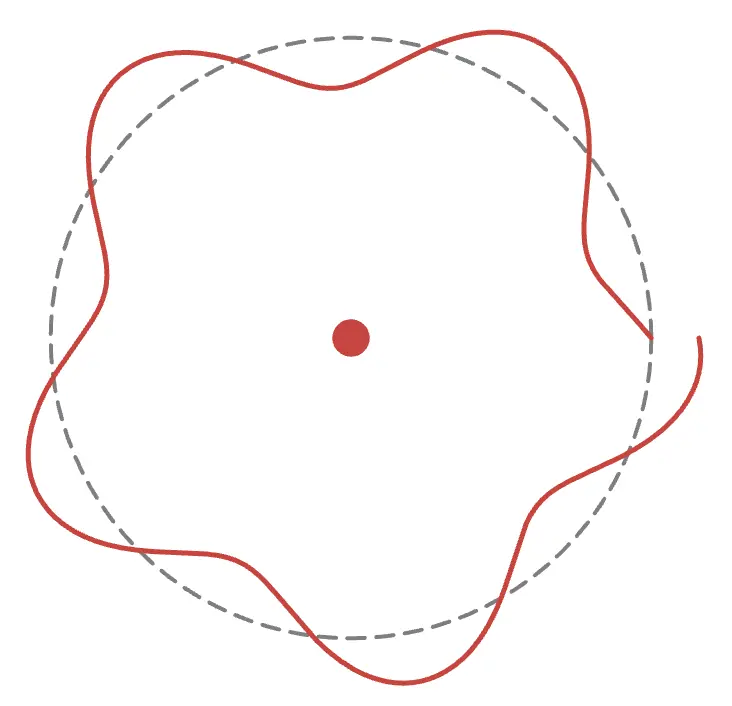

As shown in the figure above, to form a wave, thecircumference must be an integer multiple of the electron's wavelength. For example, if the circumference is an odd length, it looks like this:

The wave does not connect properly and cannot exist stably. Try adjusting the radius in the animation!

Thus, from the condition that the circumference is an integer multiple of the electron's wavelength,

is derived. Substituting the equation for matter waves into this, we can derive the quantum condition mentioned earlier! In high school physics, this equation is often referred to as the quantum condition.

This quantum condition explains why electrons do not fall into the nucleus. Moreover, it also explains why the frequencies of electromagnetic waves absorbed and emitted by electrons are discrete!

Consider an electron moving from one radius to another. The kinetic and potential energy it has at each radius are obviously different. Let be the radius when the quantum number is and be the energy of the electron.

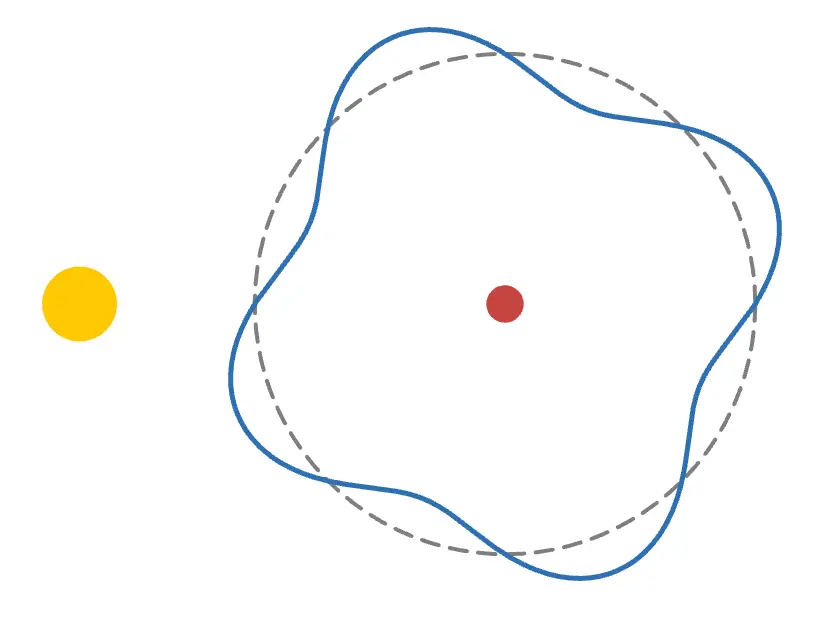

When an electron moves from to , it absorbs or emits a photon with energy equal to the difference . This explains everything! Try pressing the Absorption 1 button on the graph!

As shown in the figure above, a photon flies toward the electron,

The photon is absorbed by the electron, increasing the electron's wave by one and enlarging its radius accordingly.

The wave does not necessarily increase by one at a time. Press the Absorption 2 button to observe the wave increasing by two at once.

The photon absorbed in this case has energy , which can also be expressed using frequency as . Thus, only photons with frequencies satisfying

are absorbed.

In the case of photon emission, the reverse happens. The energy of the emitted photon is , so the frequency of the photon is

and is limited to this value.

The actual appearance of atoms

These models were based on Newtonian mechanics, but it is now known that microscopic particles behave according to quantum mechanics.

Numerous experiments have revealed that physical quantities such as the position and momentum of electrons are determined only probabilistically. Therefore, the idea that the position of electrons is always fixed has been proven incorrect.

In reality, the probability of the electron's existence is distributed like a cloud around the nucleus. For more details, please look into quantum mechanics!

In quantum mechanics, the probability of measuring physical quantities is handled using a complex function called the wave function. This wave function behaves like a wave, which is why it is called a wave function, and its wavelength matches the wavelength of matter waves. This property might explain why Bohr's model was effective at the time.