Did you know that you can calculate the value of π just by counting the number of collisions between two objects?

It sounds mysterious, but let's explore it with a simulation!

Simulation

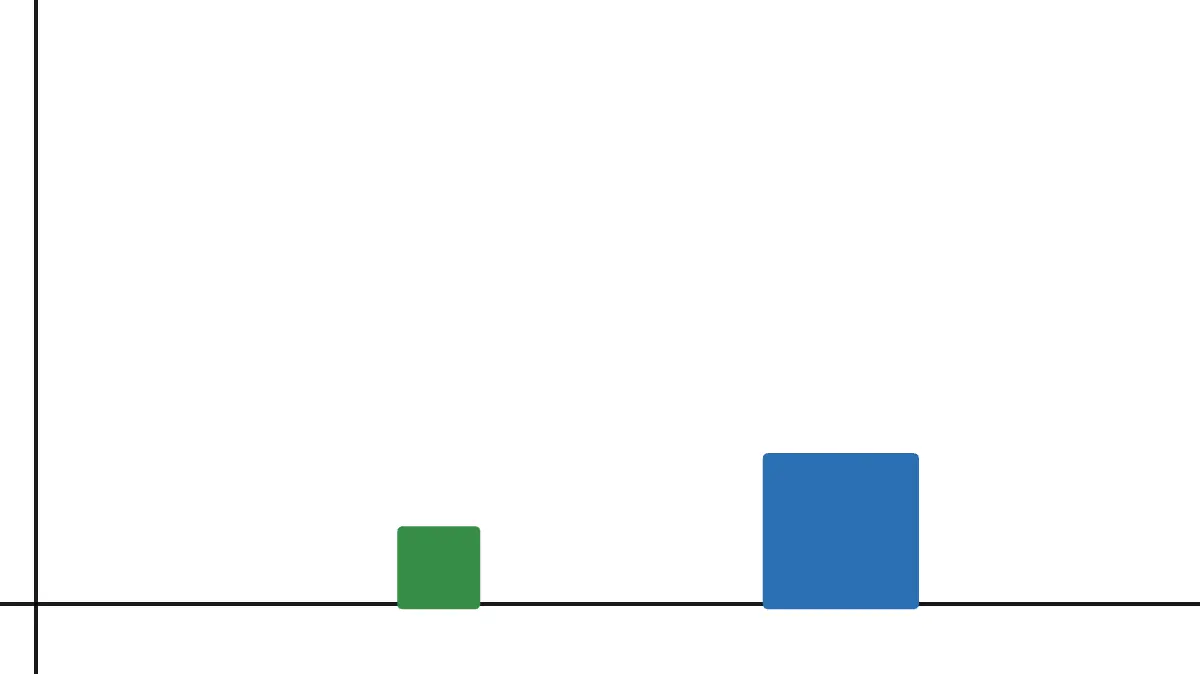

Count the number of collisions when two objects collide elastically. Start by pressing the START/STOP button and observe how many collisions occur. Then, try changing the mass ratio of the two objects and see how the number of collisions changes.

The mass ratio represents the ratio of the mass of the blue object to the green object.

Did you notice that the number of collisions corresponds to the first few digits of π?

Specifically, when the mass ratio is , the number of collisions matches the first digits of π.

Keep in mind that when the mass ratio is , the last (314th) collision takes a very long time.

In this simulation, you can observe up to . If you follow the graph link, you can simulate for any , but for , it takes too long, so it's not recommended...

Due to calculation precision and speed, this simulation takes longer than the actual collisions would in reality. Especially when the two objects are very close, collisions happen at an astonishing speed in real life.

Why Does π Appear?

Let's explore why π appears. There are various proofs, but we'll explain the most famous method using a circle.

As shown in the figure, consider the axis, and let the masses of the two objects be and their velocities be respectively. Assume that at time , .

Since the collisions between the objects and the wall are elastic, the total energy of the two objects is conserved.

This is expressed by the law of conservation of energy:

Now, let . Then:

This means that lie on the circumference of a circle with radius !

At , the point is at the rightmost position on the graph above.

Next, consider how change. Just before and after the collision between the two objects, the law of conservation of momentum holds. That is:

(where is a constant).

Thus:

This means that just before and after the collision, lie on a straight line with a slope of .

For example, after one collision, will be at the red point in the figure, which lies on the straight line with a slope of passing through the previous point.

Next, the lighter object collides with the left wall. Its velocity becomes due to the collision, so on the circle, it becomes :

Repeat this process, and it looks like this:

Here, considering that the slope of the straight line is always , the angle satisfies:

By the inscribed angle theorem:

As shown in the figure above.

Each collision adds one point. As seen in the figure, this corresponds to the number of .

Thus, the number of collisions is:

and its integer part.

When the mass ratio is , this becomes:

The number of collisions matches the first digits of !

Here, the approximation:

was used for .

Original Paper

This phenomenon became widely known after Gregory Galperin published it in his 2003 paper "PLAYING POOL WITH π."

You can read it at the following URL: here (as of March 2025).

This article left some parts simplified, but the paper dives deeper into the validity of:

and provides further insights.