Concepts like acceleration and force are fundamental in dynamics, but they can be difficult to grasp at first. This time, let's use graphs to experience acceleration and force, and understand the equation of motion that connects them!

Graph

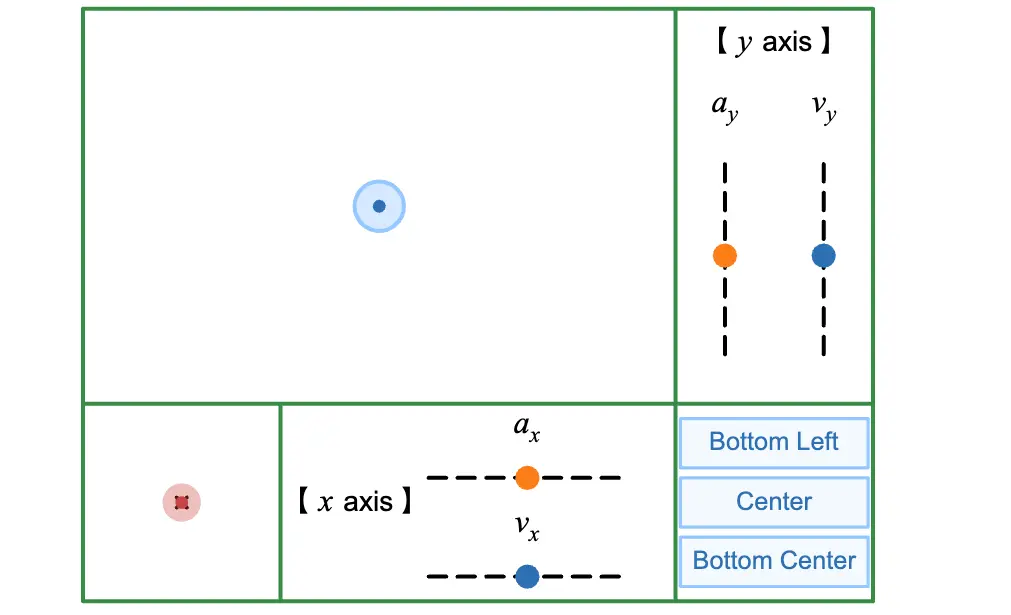

Try dragging the red dot in the bottom left! The force will be applied in the direction you drag.

You can check the acceleration and velocity in the directions using the sliders. Press the button in the bottom right to reset the object's position.

You can also adjust the object's mass using the slider. The mass will be explained later.

Turning on the switch labeled Background Circle will display a circle in the background. Try making the object go around the circle without touching the gray part of the circle! (Circular motion will be explained in another article.)

What is Acceleration?

Before understanding acceleration, let's first understand velocity.

Up to middle school, you might have learned that velocity is distance ÷ time. However, to define velocity properly, it is the rate of change of position per unit time. Unit time might sound confusing, but you can think of it as the change in position per second. For example, if an object moves 3 meters in 1 second, its velocity is 3 meters per second. This is written as . stands for second.

So, what is acceleration? Acceleration is defined as the rate of change of velocity per unit time. In other words, it represents how much velocity changes per second.

For example, if an object's initial velocity is and it changes to in , the velocity has changed by in , so the acceleration is .

You can think of acceleration as similar to pressing the accelerator in a car. When you press the accelerator, the car gradually speeds up, right? In other words, pressing the accelerator is the same as giving the car acceleration.

The unit of velocity is , but since acceleration is velocity divided by time, its unit is .

Velocity and acceleration can be rigorously defined using differentiation. Let the position of an object be , velocity be , acceleration be , and time be . Then,

In other words, velocity is the first derivative of position with respect to time, and acceleration is the first derivative of velocity with respect to time.

Another very important point is that both velocity and acceleration have directions. So far, we have considered motion in only one direction, but in reality, objects can move in various directions. In other words, velocity and acceleration are vectors that have directions.

Let velocity be , and acceleration be . Then,

is the most accurate definition of velocity and acceleration. (Position also has components in each direction, so it is a vector.)

This vector notation might be hard to visualize, but it simply means differentiating the components in each direction. In other words,

The change in velocity in the direction becomes the component of acceleration.

The magnitude of velocity is often called speed. In other words, velocity is a vector quantity, while speed is a scalar quantity without direction.

What is Force?

In physics, force refers to something that changes the motion of an object. In other words, when a force is applied to an object, its motion changes.

More specifically, applying a force to an object causes it to accelerate in the direction of the force. Let acceleration be represented by , and force by . Then,

This equation shows the relationship between force, mass, and acceleration. Here, is the mass of the object, which represents its resistance to motion. The unit of mass is . The greater the mass, the smaller the acceleration for a given force. In other words, heavier objects are harder to move.

The unit of force is , but it is commonly expressed as. For example, if a force of is applied to an object with a mass of , the object will experience an acceleration of .

In the animation above, try adjusting the force and mass to see how the acceleration changes! Notice how the acceleration always points in the direction of the force, and how increasing the mass reduces the acceleration, making the object harder to move.

This equation is known as the equation of motion. It is the cornerstone of dynamics. Let's explore it further.

Predicting Motion with the Equation of Motion

Let's focus on the components in the direction.

What Does Predicting Motion Mean?

The main goal of dynamics is to predict how an object moves. This means expressing the position of the object as a function of time .

For example, if the position of an object is given by

you can calculate the object's position at any time using this equation. For instance, at , the position is . The same logic applies to other times.

Using the equation of motion, we can determine ! This is the power of the equation of motion.

How to Calculate It

Let's first outline the general method. If it feels overwhelming, check out the specific example below for clarity.

The equation of motion is

(Since we're only considering the direction, we don't need to use vectors here.)

From this, we can find acceleration:

Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity over time. By integrating acceleration, we can find velocity:

Similarly, position is the integral of velocity:

Substituting , we get:

This allows us to calculate the position from the force .

Specific Example

Let's consider a case where the force is constant: . The equation of motion becomes:

Assume the mass is . Then, the acceleration is:

Velocity is the integral of acceleration:

The constant is determined by the initial velocity. If the initial velocity is , then:

Position is the integral of velocity:

The constant is determined by the initial position. If the initial position is , then:

For example, at , the position is .